Possible solution for nitrate pollution moving from lab to field in Nebraska

A possible solution for one form of water pollution is moving out of the lab and into the field in Nebraska, in a development that could revive some unused wells and save some towns a lot of money.

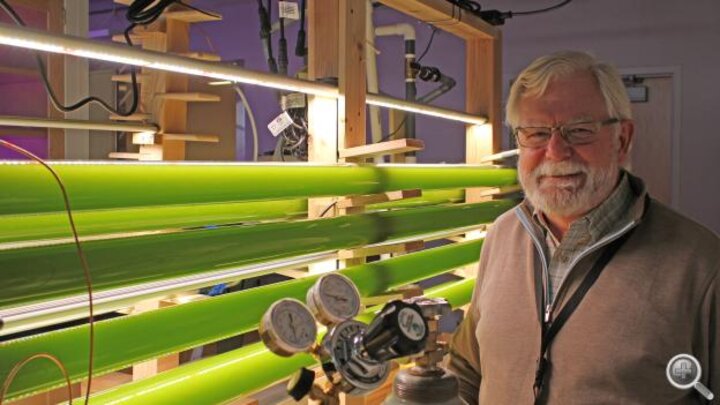

In a nondescript, off-white room on the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Innovation Campus, Paul Black shows off what look like a series of water-filled glass hamster tubes in brilliant red, fuchsia, and green hues.

“What we’re testing here is wavelength… we’re testing a combination of red light, blue light, blue and red together, and then plain white light. What we’re trying to do is maximize growth,” Black explained.

What Black is growing is algae -- the slimy green stuff that grows in ponds, fed by runoff of nitrogen fertilizer from farm fields and other sources.

Black chairs UNL’s Biochemistry Department and is a founding member of a company called Vestal W20, which is trying to use algae to remove excess nitrates out of water.

“What’s happened over the hundred-plus years of putting nitrogen fertilizer on our fields is that the 40-50 percent of the nitrogen that was not taken up by the plants now ultimately leaches down into the groundwater,” he said.

Too much nitrate in the water can cause problems like difficulty conceiving in humans and other animals, and methemoglobinemia -- blue baby syndrome -- a treatable condition where red blood cells don’t carry enough oxygen to young bodies. The Environmental Protection Agency has set a limit on nitrates in drinking water of 10 parts per million.

Black said passing nitrate-polluted water through algae and adding carbon dioxide under the right lighting for photosynthesis can solve the problem.

“We can start out with 100 parts per million or 200 parts per million of nitrate, and over a four-to-five day period, we can bring it down to less than one,” Black said.

What’s more, the algae can then produce oil, which could be used as an alternative fuel, and other biomass, which could be ground up and used as fertilizer.

Black has been experimenting with this process for almost 10 years. So far, it’s been at laboratory scale – first with a tenth of a liter of water, now up to 500 liters. But starting next spring, the experiment will move to thousands of liters at a time. The company has signed an agreement with the city of Hickman, just south of Lincoln, to build a greenhouse and process water from a well where the water exceeds EPA limits and contains 27 parts per million of nitrates.

Hickman City Administrator Silas Clarke said the city no longer uses that well.

“We actually have four other wells. We have two shallow wells that sit around 5 parts per million on nitrates – again, the top level being 10 parts per million. And then we have two deeper wells and those wells do not have any nitrates in them. But then again the water sat on the rock for so long that it’s been picking up iron and manganese, which causes discoloration issues and some other issues. And so Hickman has actually put in a removal system for iron and manganese,” Clarke said.

Clarke said it would help municipalities like Hickman if Vestal’s technology works.

“If we could get to a point of putting this well back in service, we know there’s good water under there. But it is in fact high in nitrates. So I think it could be good for the city of Hickman and it could be good for the municipal water supplies across the state,” he said.

Vestal founder Vern Powers, former mayor of Hastings, said the hope is to start in Hickman next spring and expand from there.

“Since it’s starting to get cold now, and snow, we thought let’s just hold off until Spring. So we’re going to hold off on Spring on this now, but we’ve got three or four cities lined up. We’ve got a whole lot of cities that I’m kind of holding at bay because I want to get three or four of these working, bullet-proof, and then address the other ones,” Powers said.

Black said using algae could cost only 5 to 10 percent as much as the conventional technology of reverse osmosis to treat nitrate pollution. And he said there’s a big potential market for the technology, which competitors in other states are working on as well.

“You look at the maps. Nebraska’s the epicenter of the nitrates in the water in the Midwest,” Black said.

And Black said nitrate pollution causes problems downstream as well.

“Take a look at the alluvial plain and the “dead zone” in the Mississippi Delta. When is that most problematic? It’s after fertilizer application in the fields. Because it all gets in now to the surface water and moves downstream,” he said.

Addressing those problems using the technology Vestal’s developing could produce a huge market. Black says the biggest hurdle is money. So far, the company has gotten about $3 million from the federal government and $400,000 from the state, in addition to more than $600,000 Powers has put into the project. Powers says the research could cost up to $10 million, but they’re prepared for that.

Black said the second biggest hurdle is making sure the process that works in the lab still works on the scale that will be required to treat a city’s water.

“We continue to scale because we need to get to a point where we can get it to a point of saying ‘Well, let’s try 1,000 gallons per minute. Or let’s try 5,000 gallons per minute.’ Do we have gushers that are going to work that good? Or are we going to hit a brick wall? And at the end of the day we don’t know ‘til we try,” Black said.

But Black said he’s optimistic, based on how the research has progressed using larger and larger volumes of water.

“It just gets better. So as we scale up, I have no doubt that we’re going to see this in a highly productive way. And I think we’re going to get better at it,” Black said.

Sometime next year, after the snow melts, people will be able to see if that holds true for the next stage of the project.

by Fred Knapp, Reporter/Producer, NET News